Naive boosters and smart doomsters

Sam Bowman’s post on boosters and doomsters lit up the Internet as people excitedly sorted themselves into the two new tribes. I’m going to divide those two groups further, to explore how and why they disagree.

He gave the label ‘boosters’ to those who believe that we can achieve much higher growth. ‘Doomsters’, on the other hand, are those who believe such efforts are futile.

Both sides have a point. Doomsters can point to political constraints that make it difficult to deliver policy wins in the most important areas. But boosters, if they are skilled, can find ways around these constraints.

Here’s one way to look at it:

Naive doomsters blindly reject the possibility of growth under any circumstances. Equally, naive boosters think that just demanding growth and doing anything that seems growthy will deliver the growth they want. They neglect the political limits to what is achievable.

Smart boosters know, like smart doomsters, that higher growth is difficult. But the difference is that smart boosters believe that growth is possible.

The naive boosters are sometimes right: sometimes, reform is easy. New cycling infrastructure, for example, generates its own support as more people choose to cycle. This is a positive feedback loop, and where these exist, good policy is often just a case of using a little ‘political will’ or ‘political capital’, which is repaid quickly.

Other areas have no feedback loops, but they lack huge entrenched interest groups who lose out from more supply. Reforms to expose cosseted producers to competition are much easier when most of the voters are not employees or owners of those cosseted producers. Most people don’t own their own solar farm, so it’s easy to produce cheaper and greener electricity without making most of the voters unhappy. Again, the naive booster view is right in those narrow circumstances.

But in most areas, naive boosterism is, well, naive. This is the truth in smart doomsterism: in general, passing high impact reforms is politically difficult, even where such reforms offer large potential benefits. One reason is often that the losers notice the loss, but the winners notice much less benefit – even when the total benefits hugely outweigh the total costs. That makes it much easier for the losers to organize to reverse the reform – or block it in the first place. This type of ‘collective action problem’ was identified by Mancur Olson.

Housing is an area with many negative feedback loops, because so many people own the scarce factor for production of housing services: their own home. Allowing more housing generally just creates more opposition as the new residents add their voices to the NIMBY chorus. Some residents of the first phase of King Charles III’s development of Poundbury objected to the second phase.

Surveying recent decades, it may seem that smart doomsterism has clearly been empirically validated. Growth is hard, we may conclude, because we can see it has not happened recently. But induction is a perilous way to reason: it works until it doesn’t. Looking at Britain in the 1970s, many thought that Mrs Thatcher’s reforms were impossible. Many serious people predicted that she would not manage to get change. But she did.

Both types of boosters are right that many areas of the economy have surprising amounts of inefficiency which could be improved with better policy. I suggested in my last post that we could potentially raise UK GDP per head by something like 50% if we were to fix them all.

What’s more, much of this inefficiency has been growing over time. In the 1930s, the UK had very little gap between the cost of building a house, and the price it sold for. The same is still true of rapidly growing cities like Atlanta today, which allow plentiful housing to be built. But the UK’s housing shortage has grown steadily worse since the 1940s, so that the total market value of UK housing currently exceeds what it would cost to build it all today by about £4 trillion. We have failed to fix this ever-worsening problem, which causes enormous damage to human welfare.

The shortage of housing, particularly near to the most productive firms, has grown ever worse over time, because the badly-written mess of planning laws that have caused that shortage have not been fixed.

Of course, no government anywhere in the developed world has managed to completely abolish planning or zoning restrictions in recent times. One reason is that the ‘externalities’ or spillover effects imposed on nearby residents by development are often very large. Even the most hardcore YIMBY can occasionally be driven to complain to their local government about noisy construction work waking them up at hours when such work is prohibited.

Perhaps a still more important impediment to abolition is that its cost would be quickly, visibly and viscerally pulled forward – ‘discounted’ or ‘capitalized’ – into decreases in current house prices. In other words, credibly abolishing restrictions would lead to an enormous house price crash as houses were frantically offered for sale by those who foresaw the impending flood of housing supply, swiftly followed by those alarmed by the trend of declining prices. Two thirds of voters are homeowners: the political backlash as this group saw its asset wealth evaporating before its eyes would be extraordinarily powerful.

By contrast, the benefits of planning abolition would become visible more slowly. There is no market that visibly capitalizes the benefits of planning reform – the increased future earnings and living standards of all the current renters and younger homeowners who will, over the medium term, benefit most from building more homes – into a price today. Rents will go down only slowly, as the new homes are actually built over many years. And the increased earnings from letting people live where they are most productive and happiest will also only happen at the speed of building new homes.

So those benefits are much less visible than the costs. These are the horns of the dilemma on which planning reformers are caught. Too much too quickly will never happen. Too little will have only a small effect, and leave exactly the same problem for the next government.

As I said above, those who think that fixing this stuff is easy are failing to take into account the very substantial political limits on what can get done. Doomsters are right about this. But there is no iron law of the universe that reform can only distribute costs visibly and benefits invisibly. There could be win-win, or at least nearly win-win, ways forward, in many sectors, because the current deadweight losses are so huge, and clever policy engineering can make change much easier.

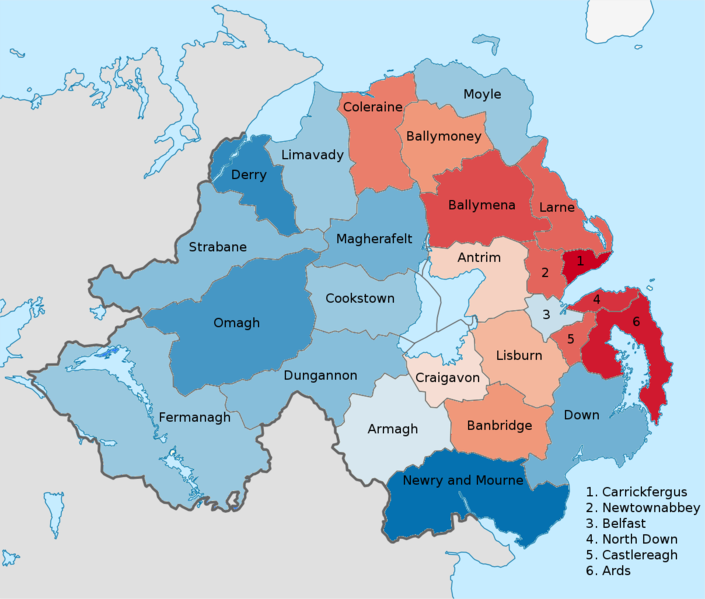

One way to do that is to make the benefits more salient, and ensure they flow in a way that encourages people to speak up in support. But smart boosters have other tools in their arsenal. Constructive ambiguity can sometimes be very helpful in building winning coalitions for change. Intelligent wording can help you unite more people behind your reform. Few of them will be interested in the detailed nitty gritty of the final implementation. Constructive ambiguity was a key tool in getting the Unionists and Republicans to agree during the Northern Ireland peace process. Blair’s chief of staff, Jonathan Powell, wrote that the ‘Unionists and the Republicans just weren’t ready to reach an agreement on it. Instead we had to reach for language that could be interpreted in different ways by the two sides.’

Market driven or opt-in reforms can also create constructive uncertainty about how much effect they will have. Thus, like the creation of 401(k)s, they can glide past initial potential opposition and then generate the effect of a snowball rolling downhill, gathering mass until it finally has irresistible momentum.

Liz Truss’s new Government has less than two years to make a noticeable difference before the next election. There are many broken sectors where it is difficult to envisage large-scale improvement in that time. But there are a few levers to pull that could start to show big benefits before then. They include housing and planning, childcare, high skilled immigration, and reducing taxes on new physical investment.

They also include fixing the broken incentives within HM Treasury. Under current Treasury metrics, global thermonuclear war could be seen as a positive. It might reduce tax revenues to zero, which the Treasury considers to be bad. But it would also reduce spending to zero, which in Treasury eyes is strictly better.

Previous Governments, which included many smart doomsters, seem to have made little serious effort to improve many of those areas. They may have expressed an intention to do something about some of them. They may even have tried a White Paper or two, like Boris Johnson’s 2020 White Paper on planning reform. But those attempts generally lacked sufficient preparation and work to be feasible reforms. The sectors haven’t been fixed yet because they are hard to fix. And many of those obstacles are political. It takes painstaking work to design things that can work in practice and in politics, and to build a political coalition of support that will help you drive them through. Without that groundwork, change is very difficult.

Will reform efforts succeed? I prefer optimism. Reformers have succeeded in peacefully sidelining or skilfully co-opting rentier groups many times in the history of the UK, from the Great Reform Act onwards. The doomsters are right that we cannot just point at broken areas of the economy, wave a magic wand, and fix them. It takes hard, detailed, competent work. If it didn't, someone would already have done it. But there are enough encouraging signs that people are getting serious about fixing growth to imply that the smart doomsters may, finally, be wrong again this time.

Excellent post, John. I think I find myself straddled between the smart boosters and doomsters.

I am certain that there is a great deal of growth up for grabs, particularly given how many regions are behind economic growth 'frontiers'. I.e. less productive regions can borrow productivity growth methods from other regions that first invented technologies, or found efficiencies before everyone else.

But on the other hand, there are fundamental reasons these gaps exist. Demographics and political structures that are stacked against reform are the source of my doomsterist streak, not the lack of available growth opportunity.

It is cracking this nut - through quietly and subtlety reforming the incentive structures of these problem areas in fundamental ways - that will lead to the victory of growth, and the victory of the boosters over the doomsters.

Where was the entrenched opposition to allowing people to add new storeys to their homes by right? Yes people were busy worrying about COVID at the time, but the change to permitted development went through with little fanfare. The key to planning reform seems to be doing it in a way that focuses the benefits on existing homeowners.

So accessory dwelling units and mansard roofs. Later maybe we can put it on a proper statutory footing and gradually create a proper zoning system...

https://cerereanscratchpad.blogspot.com/2022/07/forget-greenbelt-yimbys-should-focus-on.html